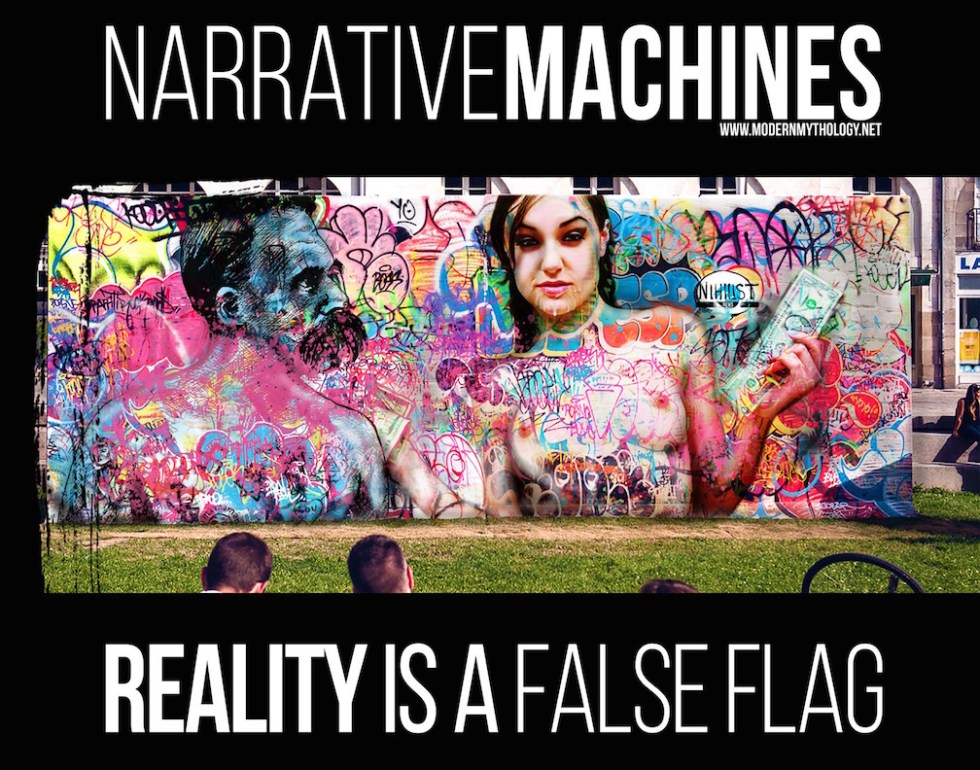

photo by Bart Nagel

“What I had seen of the war had been a computer generated simulation” J.P. Barlow

by John Perry Barlow, introduction by R.U. Sirius

After the confident declarations of inevitable cyberpunk youth takeover in the first edition of Mondo 2000 and the philosophically trippy and mostly utopian read on Virtual Reality in #2, it was inevitable that affairs in the world would bring us crashing down to earth… at least a little. The third edition revolved largely around the hacker crackdown that was called Operation Sundevil — a situation in which a confused and clueless law enforcement establishment pursued crimes they didn’t understand on a terrain they hadn’t realized existed.

Issues #4 and #5 found us, meanwhile, reacting to Operation Desert Storm — the first full-on return to American Triumphalism since the Vietnam war turned sour in… what?… 1968? We weren’t watching much TV at the Mondo house/office but I remember CNN being on as a sort of background phenomenon during the run-up to the war.

This was the first time the media’s inevitable participation in the sort of unquestioning jingoist war propaganda that we’re always treated to during the run-up to a major intervention was ginned up by computerized special effects. And prideful current and former military leaders sharing technical details about shiny new weapons systems would bring irresistible frisson to certain types of technophiles — Smart bombs! — Wowee! Well, as John Fogerty sang, “It ain’t me.”

President George H.W. Bush even enunciated the idea of a “New World Order” spawning a million new byzantine conspiracy theories that have iterated and turned into ever-weirder and more complex alternative realities since.

As for me, I organized a radio show called “New World Disorder” on KALX fm in Berkeley with Don Joyce from Negativland and wrote an editorial in #4, also titled “New World Disorder.”

In issue #5, John Perry Barlow took up the antiwar banner identifying Desert Storm as the first Virtual War in the layout and text provided below.

Don’t get me wrong. Mondo wasn’t freakin’ Mother Jones or something. The rest of the edition featured an erotic quantum physics limerick; newer smart drugs; the cyber-surrealism of Mark Leyner in the immediate aftermath of his incomparable Et Tu, Babe; a gigantic section on industrial music; Mark Dery deconstructing machine sex and sex machines; a much criticized spread with lovely ladies with their bare nipples shining through microchips; and speaking of smart bombshells, that cover you see is Dr. Fiorella Terenzi who talked to us about her music of the galaxies. I was told later that every male in the building — except me — stopped work that afternoon to gather in the art room where the interview took place. Was I noble? No, I was shut in my office working on something completely unaware. I was the editor-in-chief and nobody told me a damn thing.

Oh it might also be worth mentioning that we scrambled the names of two avant-garde guitarists on the cover, leading to embarrassment followed by some theorizing about “Art Damage” in the next edition.

Anyway, here’s “Virtual Nintendo” by John Perry Barlow from issue #5 of Mondo 2000.Â

R.U. Sirius

Below the scan of the actual magazine, you will find a purely textual version of the article.

VIRTUAL NINTENDO

by John Perry Barlow

It is precisely when it appears most truthful that the image is most diabolical.

-Jean Baudrillard

Like most Americans last February, I was hooked on the new CNN sports series War in the Gulf. It didn’t sound strange to me when a friend said he didn’t know whether he wanted to watch the War or the Lakers game that evening. They were fairly indistinguishable. Both commentated by fatuous men well removed from the action. Indeed, in the case of the War, one wondered if there even was any action. The closest one got to that was the occasional footage of people scurrying around in the darkness following a Scud warning, followed by a blurry flash of distant fireworks as the Patriot took out the Scud.

Which was, in a way, a perfect metaphor for the abstraction and bloodlessness of this new form of combat. A missile would emerge without any tangible point of origin, its senders anonymous and devoid of human characteristics. A machine would detect it, another would plot its trajectory, and a third would rush out to kill it. It was like an academic argument. Flesh and bone were miles away from anything that might rend them.

Finally, after weeks of this shadowboxing, it was determined that the map of Kuwait had been sufficiently revised that it was now safe to send in live Americans. Personally, I still had such fear of the Republican Guard that I thought we should soften them some more. What I thought we faced was an army as large as ours, toughened by almost a decade of the nastiest combat since World War I, comprised of Muslim fanatics, each convinced that death in battle was just a quicker trip to Paradise. Certainly more than a match for a bunch of rag-tag American kids who’d joined the military because they couldn’t get a job at the 7-11. Read more “The First Virtual War by J.P. Barlow from MONDO 2000 #5”