by R.U. Sirius

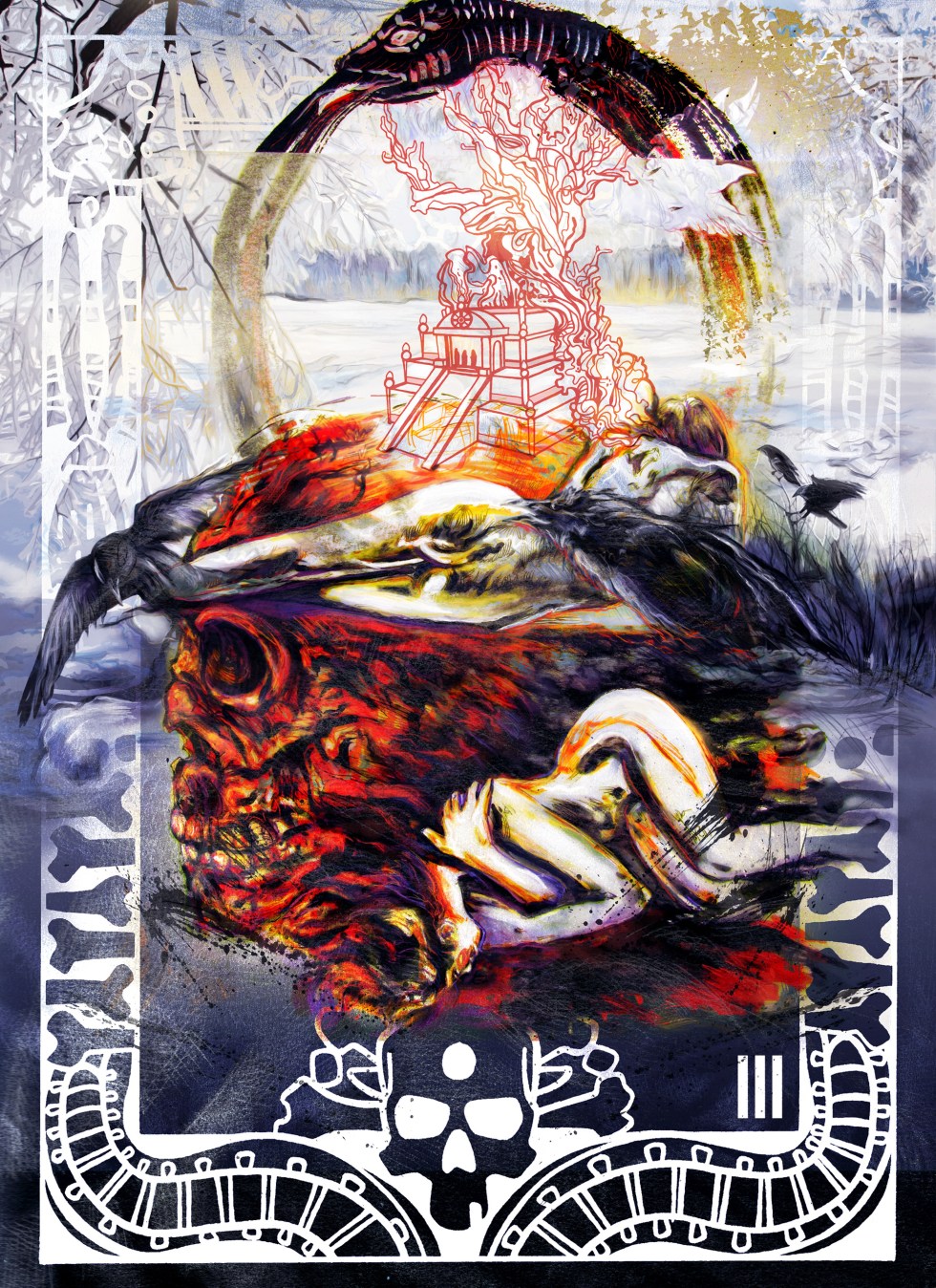

artwork by Jamie Curcio

Jamie Curcio is a brilliant artist and cultural theorist or something like that… but even, thankfully, harder to pin down.

In any case, he is one hell of a writer and thinker, mixing together all kinds of favorite MONDOid memes — the ups and downs of post-whatever philosophies, the over-the-edges of avant cultural works, media narratives and quasi-apocalyptic hysterias and — perhaps most charmingly — he is obsessed with David Bowie.

Books include Narrative Machines: Modern Myth, Revolution and Propaganda, Party At The World’s End (Fallen Cycle, Volume One) and the upcoming Masks: Bowie and Artists of Artifice, which is in progress.

I interviewed Curcio mainly about Narrative Machines and the upcoming Bowie book.

R.U. SIRIUS: Your book Narrative Machines provides a discourse about the distorting effects of a sort of mediated hall of mirrors and decentering of identity. This sort of thing has been active for a very long time, even before the internet made its growth “exponential.” From whence comes the recognition that the contingency of our narratives is more useful to the “right” than the “left”… if true?

Also, there was a ‘90s idea that a sufficiently advanced technology would sort-of blow through the rupturing aspect of it all — that the dissipating structures would eventually cohere as a higher evolutionary order. Is there any use for that sort of hopeful perspective today?

JAMIE CURCIO: Pessimism and realism have a complicated relationship. That’s one of the things I was trying to come to terms with in working on Narrative Machines. So let me say, if being pessimistic is going to shut people down, then I’m not going to say it’s a virtue.

But it’s also hard to really take an account of the problems on the horizon for our civilization, and our collective inability or unwillingness to deal with it, and not recognize how blinding optimism about the “revelatory power of the new” can be. Accelerationists often forget just how dumb the perpetual rush toward the new can be.

People can read that statement in a Right or a Left way — they’ll differ in terms of looking for a solution, or in what “our civilization” means. Everyone seems to think the barbarians are at the gates, whether it’s the Fascists and Russian oligarchs, or the immigrants and cultural Marxists brainwashing the children. It’s clear which I think is more absurd, but in either case, it’s a war of myth. We can joke about memewar, but I think we need to recognize the ways that it isn’t a joke, or at least, the way that it’s a continuation of propagandist methods that are hardly new.

There’s a kind of messianism and eschatology that runs through both the “Right” and “Left,” the idea that a political ideology itself can fix anything. Robert Anton Wilson wrote about this plenty. I think he was ahead of the curve in many ways, for all that it’s worth. And he was adamant about remaining optimistic.

To me, the silver lining is that if the analogy of the effect on culture the printing press had, and now with the internet, then there’s reason to believe the end isn’t nigh in that regard. Things are looking dark, but if we’re talking about bot armies and the Russian use of postmodern methods in their propaganda — all is not lost. It just emphasizes the importance of studying “useless” things like philosophy and art.

On the other hand, the way that unfettered capitalism is likely to consume the planet, or at least its habitability for a great number of species including, ultimately, ourselves… that’s another story. For all we know, that ship has already sailed. The only way out, if there is one, is through. We’re committed to carry the experiments of the past into the future — just look at how the problems and solutions of a century ago continue to get resurrected. Fascism, Communism, Liberalism. The three ideologies that arose from the ashes of WW 1.

I should add, I happen to think compassion should guide our actions toward others as much as we can manage, and much Right wing ideology seems a veneer for various forms of cruelty, and I believe cruelty should be reserved for art. So my sympathies tend to run Left, but that’s different from an ideological commitment.

RUS: You take on the statistical based optimism that seems to be well-loved particularly by neoliberal sorts like Pinker. The idea is that statistics show us that human beings are improving their lot in life and becoming more well-behaved. Can you explicate your view a bit?

JC: I was taken by John Grey’s argument on this subject in The Soul of the Marionette, and so while I didn’t just reproduce it, I would say it helped me put a pre-existing line of thought in order. In short, I investigate the Progressive certainty that everything is improving all the time is very much based both on our selective interpretation of the facts, and our situation in terms of a particular narrative we have constructed about our place in history. There have been undeniable benefits per capita in the past 100 years regarding the marriage of technology and capitalism. Will that read the same in 100 years? I’m not so sure.

RUS: I think underlying the technotopian hope of the late 20th Century was the idea that this mostly white and American eruption at the end of the 20th century could use tech to deliver an awesomely improving world and you could elide the blowback from centuries of colonialism and racism. It’s not an entirely bad idea… to avoid conflict.

JC: It definitely tends to overlook the role of inertia in a culture, or of a true reckoning with the past, why that keeps repeating itself through us. Time may be accumulative but the behavior of complex systems is generally not linear.

RUS: You deal in Narrative Machines with questions of revolution… and how it doesn’t tend to deliver on its hopes. Looking at the Arab Spring, would you say that any movement now just accelerates confusion. There’s no interregnum of hope?

The broader question about revolution usually not improving things… does this leave us with neoliberalism with its economic domination, total surveillance and constant war… or nationalism?

JC: I use the Arab Spring as an example. What struck me about it was how clearly it supports the idea of “revolution” as very literal — going around and around, forever. There is a sense of Frazier’s Golden Bough here, each King deposed by the King who will one day be deposed. Though that’s a bit reductive, it is hard to find examples of revolution going well for “the people” long term. It’s generally good for some people, and not others. To the extent that revolutions are a power play, they just reshuffle the cards. There’s a lot in Marxist thought about getting beyond that problem… which we definitely haven’t see play out in reality. The day of the revolution is one thing, but there’s always the day after. But that doesn’t necessarily mean everything is hopeless — we still affect one another, things do actually change.

But my ultimate focus in that book isn’t political, even though it deals so much in political ideological terms. It’s all a backhanded argument for an art movement, really…

RUS: I want to get to the central discourse in Narrative Machines… the centrality of mythos and of narrative. The down home aspect of this is the question of people “voting against their own interests.” I long for materialism in politics, to be blunt. It seems pretty much implausible. Tribalism seems on the rise.

JC: One of the central ideas in Narrative Machines is in the title. We don’t simply record one another and repeat snatches of what we’ve heard, so in that sense we’re not “machines,” but we do something very similar to this — we’re born into a specific place and time, and everything from the structure of our language to the behaviors of those around us is all we have to construct our “realities” out of. It’s at once a very claustrophobic idea and a freeing one I think, depending how you take it.

So… what did I mean by an art movement? Art first appears in the context of religion and magic. If aesthetic is a carrier of many of our implicit assumptions about the world we live in, it turns everything on its head. All medias are propagandic. I started looking at that in Narrative Machines and have carried it on to Masks: Bowie and Artists of Artifice.

The first book, which is out now, is broader and more abstract dealing with these ideas. By the time I came to Masks I was influenced by an insight brought on by Bowie’s death and the three years of writing and research I’d done for Narrative Machines and thought it would be good to really focus in on the role of art within the explicit context of specific approaches to the problems it raises. That should be published in 2019.

RUS: Yes… If you look at Burroughs, Kathy Acker and various other avant-gardists you get a kind of exploded narrative. But we bring our narratives to them. We get the avant-heroes… like Bowie, also. Exploded narrative was supposed to free our minds and our asses would follow…

JC: Very much so. And there’s a number of ego traps in there. I think in the 70s Bowie would have liked us to imagine that when he got off stage he took off his mask and there’s just a formless, shifting void underneath.

Yet in a generally Buddhist sense, I suppose it’s also kind of true…

R.U. Sirius: In this time of alt-right and the at-least partly legitimate panic around it, writing about Yukio Mishima in the Bowie book must have had a certain frisson. You’re complicating the idea that only idiots get involved in nationalism. Did that enter into your excitement about an essay that discusses Bowie and Mishima?

JC: I think part of what interested me in that regard is the fact that, at least at times, both dealt in similar aesthetics. Of course, one incarnation of Bowie talked about Hitler and Himmler with almost obsessive frequency, but the real connections are more subtle and foundational. Aside from Mishima having at least some deference for traditional constraints on aesthetics, and Bowie being fairly heretical in his bending and warping of tradition to his own use… But for being so regressive, Mishima was also paradoxically modern. And more prosaically, Bowie was a big fan of Mishima. Yet they also couldn’t have been more different, like night and day. I found that ambiguity interesting.

Also, the current political moment deals a great bit in the role of irony, satire, and role playing, and I thought it was absolutely essential to get down to the bottom of the relationship between politics and aesthetics, bringing them both together within the context of performance.

RUS: Bowie’s masks were more hypermediated. And Mishima made it all too physical. Did Mishima intentionally debase himself as part of his suicidal final “performance”/coup attempt? I mean, standing on a balcony like Mussolini?!

JC: He had a very difficult time telling fantasy from reality — which is actually not necessarily a bad trait for an artist to have, since the two are always troublingly linked. He had to compose his death like a scene from a book. The sense of postmodern performance art runs through all of it, even though the blood was real. I don’t think he saw it as a debasement, anyway. Even despite their overt failure to accomplish the tatenokai’s political goals, it’s my premise that the deeper driving force here was aesthetic. That matches the thesis in the two main Mishima biographies, Stokes’ and Nathan’s.

The “Mishima incident” was so over the top, though he’s mostly faded from the world in a way Bowie probably won’t. I imagine a lot of readers here will need to Google it, and that’s kind of the final statement here, I think. Mishima used to be almost unthinkably popular for an author, given our now modern expectation of how far a writer can climb. Sadly, I think Gore Vidal’s lamentations about the “death of the author” are more accurate than Barthes, outside the literati. The role of mediation is still debatable, but no one any longer imagines an author can be a rockstar, even if we easily imagine the opposite.

However, we also should remember that Mishima was romanticizing ideas that weren’t that uncommon in pre WW2 Japan. So, the level of drama and the surreal nature of the act, as well as the aesthetic obsession were all Mishima, but the ideology was hardly his invention. Every boy growing up when he did would have been inundated with ultranationalism. But Japan changed, and in this regard he refused to.

RUS: This makes me think also of the live suicide or murder as the ultimate performance art… Bowie and Eno got into it…

JC: The focus of their second major period of collaboration was all about this, or at least it was one of Bowie’s major preoccupations. The transcendence of taboos, outsider art, and the idea of an artist’s work, their corpus, being the same as the literal meaning of that word — a corpse. I think anyone will recognize in Bowie by this point that art had become a safer rather than a more dangerous way to explore such ideas. No one I’m aware of was particularly worried he was going to go around killing anyone. “Don’t mind the bodies. They’re PR for the album — just go with it.”

RUS: With Bowie there was that strange idea of making an actual Minotaur. I imagine that would have made his reputation more freakish than he might have wanted for his family to live with…

JC: As I recall, a fan offered his body after he died, to have a bull head sewn in place of his own. Somehow I would imagine his family would take it in stride, he said he’d house it on a Greek island after all — but yeah, I laughed pretty hard when I first read about it. Of course, we always have to keep in mind how much he liked playing with the press. Either option is kind of equally plausible.

RUS: Is there something suicidal about our realization or virtualization of the way that our place in the world is performative? Does one need increasingly desperate strategies in a mass performing society?

JC: It’s funny you should ask that. One of the plotlines in Party At The World’s End begins with a character saying that if you ever want to make it as an artist, you’ve got to bomb a shopping mall. This leads into a critique of countercultural tendencies. When you write satire it’s always a little hard to know how it’ll be taken, especially these days. So, in a sense I would say yes.

RUS: In terms of Bowie and Masks I found myself thinking about this text I wrote for Mondo Vanilli about Inauthentic Authenticity versus Authentic Inauthenticity, which – in its simple form – is about not pretending anything we present is unmediated. I compared Springsteen and Bowie. Bowie dove right into those contradictions explicitly.

Bowie is such the darling of the intellectual who can talk Baudrillard or Bataille and mix it with a love of pop. He’s probably the only one who was explicitly all there with us… (I mean in terms of pop musicians).

JC: I think it’s remarkable that the one period of Bowie’s career where he really lost his way was the period in the 80s when he tried to play a “regular guy.” Springsteen as a counter example there is apt. When Bowie tries to do it, it’s like the uncanny valley with a robot that seems close to human, and yet so far. When he was at his most artificial — somehow we read authenticity there.

RUS: I also found myself thinking of Acker’s emphasis of the body as a site for reality and yet still changeable. Genesis P-Orridge suggested something even stranger… hir body as a cut-up.

I suppose there is the modern primitive idea expressed by McKenna too. That we would be “dancing around the campfire in in our penis sheaths” but meanwhile nanotech would be delivering our needs and we would have all of the information in the world on chips behind our eyes. Not sure what I’m asking you for there but just throwing it out as a thought. The body as the ultimate source of identity… post-narrative perhaps.

JC: The body is certainly a point where fantasy and reality intersect, and increasingly the ability of the one to determine the other. There’s a passage I quote in Kobe Abe’s The Face of Another that gets at this tension,

“But it isn’t particularly strange to respect content more than appearance, is it?”

“Do you mean respecting contents that have no container? I have no faith in that. As far as I’m concerned I firmly believe that man’s soul is housed in his skin.”

“Metaphorically speaking, of course…”

“It’s no metaphor…,” he continued soothingly, but in a conclusive tone. “Man’s soul is in his skin. I believe that to the letter.”

The internet is in a sense a “place” where we can all be faceless. This has its own social ramifications.

RUS: You write both fiction and nonfiction. One has the sense that these categories bend for you and feed off of one and other.

JC: This is why I find writing nonfiction almost like a dressed up version of the research being done for my next fiction book. My biggest projects right now are Masks and Tales From When I Had A Face, one a nonfiction exploration of certain themes in art as they affect famous artists, the other an existential fairy tale that draws on much of the same source material. I rarely plan it this way, but it seems to happen of its own volition. It’s true: I have very little control once the creative instinct takes over. I’m perpetually surprised at what I get, for better and worse.

It winds up being just different ways of communicating ideas anyhow. I’d like to think we gain a certain wisdom in recognizing the role myths and fictions play in our daily lives, even if we never get “outside” them. We just outgrow some stories, and hold on to others