An interview with Steven L. Davis, co-author of The Most Dangerous Man in America: Timothy Leary, Richard Nixon and the Hunt for the Fugitive King of LSD.

On September 13, 1970, Timothy Leary escaped from a low security California prison by pulling himself on a high wire over a 12 foot chain linked fence topped with barbed wire. He was ferreted underground by the radical Weather Underground who helped him escape America. He ended up in Algeria with an exiled chapter of the Black Panther Party lead by Eldridge Cleaver.

All MONDO readers probably know this, but I thought I’d set the scene a bit.

While I was a participant in the late 1960s counterculture — to the extent that a high school student in a smallish town could be — I wasn’t particularly obsessed with Leary. I enjoyed reading his occasional piece in the underground press, but Abbie Hoffman was more my thing. Until the escape. After that, I developed a lifelong interest in his action adventure episode and how it impacted on his philosophical ideas.

That’s why I was excited to learn of the publication of The Most Dangerous Man in America: Timothy Leary, Richard Nixon and the Hunt for the Fugitive King of LSD by Bill Minutaglio and Steve Davis. The book doesn’t disappoint. The narrative is in present tense and fast forward. It’s a ripping yarn that bounces back and forth between Leary’s life on the lam and President Richard Nixon’s own personal delirium as he copes with the Vietnam war, extreme rebellion in the streets of America and his own obsession with capturing Leary.

For those MONDO readers, who have followed Leary’s philosophical musings over the years, this period is kind of the last phase of Tim’s cosmic hippieishness. He comes across as deep into mysticism; consulting the i Ching and the Tarot for strategic decisions and so forth. In some ways, his intellectual credibility would rely on things he wrote before this time and after it. And yet, I think he gained a lot, in terms of sophistication and insight from the experience, that showed up in his later writing.

I interviewed Steve Davis about the book via email

R.U. Sirius

R.U. There are a number of things that are illuminated for Leary fanatics (as many Mondo readers are) by your book. One of them is the degree to which many of the ultra-radicals of that crazy period in the early 1970s were not really Tim’s friends. Particularly the lawyer, Michael Kennedy. What can you tell us about this “alliance”?

Steve Davis: Well, you can see this alliance of “dope and dynamite,” as Michael Kennedy enjoyed calling it, play out throughout the book. In some sense both Tim and the radical left were using each other for their own purposes. For Tim, of course, the revolutionary outlaws provided the means for his escape from prison – something he wanted desperately. But then of course once he climbed over the prison fence he entered a blind maze of new prisons – and as you say, these people did not have Timothy Leary’s best interests in mind, from the Weather Undeground demanding his rhetorical fealty to their vision of a violent revolution to Eldridge Cleaver and the Black Panthers demanding that Tim renounce LSD and join them in calling for Death to the Fascists. On and on it went. Tim had to keep shape-shifting to save his own skin. He basically became a pawn of both the far left and the far right (Nixon and his cronies) during this era – and of course when everything ended and he looked back on it, he realized that the law-and-order struggles between the far left and the far right were two sides of the same coin. I think the experience made him suspicious of any alliance after that. Hell, it would do the same to any of us!

R.U. There’s the scene in which the radical lawyer visits him in exile while Tim is desperate for help and the lawyer basically presents him with the bill. I know that Tim always resented having his family home in Berkeley taken to pay the legal fees.

Tim was in an incredibly vulnerable position at the time of this visit – he was sitting in a Swiss jail awaiting possible extradition to the U.S. (not to give too much of the plot away, but, yeah, he manages to slip away from this particular snare – with an outpouring of help from writers and thinkers and thousands of regular folks all over the world.) And so, here’s Tim, in a dungeon, really, feeling nearly certain that any day he’ll be sent back to the US in chains.

To set the scene a little bit further, let’s note that Tim had earlier been trapped in Algeria, for months, with an increasingly ominous-sounding Eldridge Cleaver, yet Kennedy had completely ignored Tim’s increasingly desperate appeals for help. But now that he’s in a Swiss jail, Kennedy sends his partner, Joe Rhine, to Switzerland. But the visit had nothing to do with providing aid. Rhine was there for two reasons: one was to check up on Tim and make sure he wasn’t blabbing to people – especially the FBI – or cutting any deals by revealing that Kennedy had helped orchestrate his escape from prison. And then the second reason, as you allude to in your question, was to basically strip Tim financially. We weren’t privy to the accounting records held by Kennedy’s law firm, but from our perspective, Tim had a damn good reason to feel that he’d been screwed over financially by Kennedy. He shouldn’t have had to surrender his home.

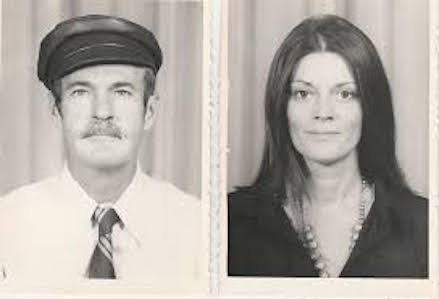

Eldridge, Timothy and Abbie

But let’s be honest and think more broadly about where the blame really lies: Tim’s home in Berkeley had been paid off. He left his adult children in charge – they were able to rent the home out and all they had to do was dedicate a portion of the collected rent to pay the taxes. Not a complicated setup, but for whatever reason, Tim’s kids proved incapable of handling that. And that’s really how the house got lost – because when it went into arrears for taxes, Kennedy had to step in and make those payments – and that’s what put Tim in a vulnerable position with Kennedy. So, you can blame Kennedy, and it’s easy to do, but we should also be thinking about Tim’s kids – and maybe his parenting.

Tim, of course, was happiest when he could just live and think and not have to worry about hustling money or paying bills. Come to think of it, that scenario sounds pretty damn appealing to many of us.

R.U.: I wonder what younger people make of that period in the early ‘70s (that were formative for me). The passion people felt about ending the war seems sort of sadly archaic. And the whole “let’s overthrow the government asap” thing has mainly shifted from left to right. How does that all speak to our time?

SD: I was born in 1963 and came of age in the 1970s and always felt like I’d just missed out on one of the greatest, most exciting time periods in American history. And that’s actually true. But I’ve come to agree with those who define the “Sixties” as the period from 1963-1974 or thereabouts. From the JFK assassination to Watergate. So in a sense, this early 70s story is really a continuation of the Sixties.

But I know what you mean about the passion for ending the war feeling sadly archaic. I was talking with a Sixties writer I admire who’s written two of the best, but overlooked, counterculture novels: Edwin “Bud” Shrake, author of Strange Peaches– about a dopesmoking antihero in Dallas at the time of the JFK assassination and Blessed McGill – a fine peyote-tinged historical novel that is the first “Absurdist Western.” Anyway, Shrake and I were talking about why people weren’t rioting in the streets at the beginning of GW Bush’s Iraq war, and he pointed out that, if we still had the draft, people damn sure well would be rioting.

And that made me realize that one of the great “triumphs” of the 1960s – ending military conscription – actually is a great failure, for three reasons: 1) we still have a draft, only it’s an unacknowledged economic draft – poor people have to “volunteer” for the military in order to gain opportunity. 2) as imperfect as the draft was, it threw different segments of society together and forced them to live together. Which moderates extremes. We’ve lost that. 3) finally, when you have an unpopular war and you’re in danger of being drafted to fight for it, you’re damn well going to protest in the streets. We’re not doing that now because it’s “the other” who is fighting those unpopular wars for us – people who have no choice because they have no other opportunities. When you think about all this, it makes you really question what the Sixties accomplished, and whether the bulk of the benefits went to the privileged, educated classes.

One last thing while I’m ranting about this – why don’t we have a constitutional amendment: any politician who votes in favor of military action must send their immediate family members to fight on the front lines. Let those fuckers fight the wars they’re voting for.

R.U. The other thing that I think many of us didn’t quite believe when Timothy alluded to it was the degree to which Richard Nixon was engaged in his persecution and capture. Tim was apparently near the top of Dick’s list.

SD: Yeah, when you hear Nixon and his aides in the White House chanting Leary’s name and Nixon bellowing “We have room in the prisons for him” that definitely proves Tim’s point about being persecuted. Actually, when we began writing this book we didn’t know any of that. I was simply drawn to this story because I liked learning about Tim and knew that this episode of his prison breakout and life on the lam was damn interesting, but very little had ever been written about it. I mean, it has surreal absurd nightmare/adventure written all over it. And with Tim’s archive now available to researchers, we figured we could get close to the story.

I’d seen some of the same things you mention here – this idea that Nixon had described Tim as “the most dangerous man in America” – which Nixon apparently enjoyed calling other people as well, most notably Daniel Ellsberg of the Pentagon Papers. But it wasn’t until we got into the archival research – along with the FBI and CIA and State Department files we were able to gain access to – not to mention the Oval Office recordings, were we able to really piece together and then understand the extent of Nixon’s Leary obsessions.

The amount of energy Nixon’s Administration invested on recapturing Leary – who was originally arrested on a minor marijuana possession charge – is stunning. You had Nixon sending his Attorney General over to Switzerland to strong-arm the Swiss into giving Leary up. You had the Secretary of State pressuring the Algerians – to the exclusion of other important diplomatic priorities in that country. In Afghanistan, a pivotal nation on the front lines of the Cold War, you had Nixon’s people gambling with our fragile diplomacy there in order to force an illegal rendition of Leary. A few months later, Afghanistan’s government collapsed. The abuse of power by Nixon and those who worked for him is unnerving – and even more so when you realize that, truthfully, Tim Leary was probably just one of probably hundreds of people Nixon was going after. Leary, for example, was never on Nixon’s “Enemies List.”

RU: At first Nixon’s animus towards Tim seemed strategic but after awhile he was really angry at Tim for not getting caught.

SD: For Nixon, like Trump (sorry, couldn’t resist) everything was personal. Honestly, I don’t think that Nixon had that much of a sense of who Leary was for the most part. He just knew him as this ex-professor, longhaired druggie-degenerate peddling LSD. But Nixon probably wouldn’t have recognized Tim if Leary had walked into the Oval Office and handed him a tab of Orange Sunshine and told the president it was a miracle cure for alcoholism.

Clearly, what really bothered Nixon was his government’s inability to deliver results, to bring him the head of Timothy Leary. It began with J. Edgar Hoover assuring everyone, “We’ll have him in ten days.” And as the Leary chase stretched across entire continents, and Tim left a trail of frustrated FBI, CIA, and State Department people behind, you can practically see Nixon growing more and more angry – just as he was in every other facet of his life at that time. This was, after all, a president who’s first reaction to thinking that the Democrats have stashed incriminating files about him at the Brookings Institution is to immediately order his aides, “Goddamn it, get in and get those files. I want it implemented on a thievery basis…You’re to break into the place—blow the safe and get it.” When you’re dealing with a madman like that, and you’ve got Timothy Leary hopscotching his way across the world, you bet Nixon kept upping the ante trying to capture him. Putting that five million dollar bail on Tim’s head felt more like a bounty.

R.U.: How would you account for him taking so much more acid the more desperate his situation became? Most of us would do the opposite, I would think.

SD: I’m not sure I have a good answer for that, but I can take a crack at it. Let’s say that Tim became really adept at managing the LSD experience, even controlling it; perhaps better than anyone else could. Given that, let’s say that Tim came to rely on the insights, on the perceptions, that he experienced while doing LSD – because he felt that those perceptions lifted him to a higher cosmic understanding than he’d had previously. And at some point, that became his dominant way of viewing the world – it led him to great thoughts and ideas.

Nothing wrong with that, right? Except that, Tim also built up a huge tolerance to LSD and so kept having to take more of it to keep pushing the edge. And while he’s busy assembling his view of humanity based on a cosmic viewpoint, he loses sight of the ground-level political intrigues that ended up threatening so much of his personal well-being.

I think Eldridge Cleaver, who was crazy in many ways but also very smart and perceptive, had a good handle on this when he noted of both Tim and Rosemary: “We’ve noticed that they’re very dangerous people because whatever the use of LSD has done to their brains, one thing that it’s very clearly done is destroyed their ability to make judgments, particularly in the area of security.” In other words, peace, love, and understanding only works if everyone else is playing that game.

RU: This is such an action adventure story, One would love to view Tim, in this situation, as a dashing romantic competent outlaw. Well he was dashing and romantic… but not altogether great at stealth and cunning.

SD:Ha, ha, yes, that’s true. It was Eldridge Cleaver who pointed that out in Algeria. If you think about Cleaver, who had a reputation as the toughest, meanest Panther – and who organized a secret mission for Tim Leary to take a trip, incognito, through the Middle East into the PLO war zone – and Leary shows up at the airport with a button on his cap that says “Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out,” you can get a sense of Tim’s inability to engage in subterfuge – and how frustrating that was to Cleaver and others on the militant left. The truth about Tim is that he was not made to live underground – he couldn’t stay there. He managed to surface several times and, in that dashing romantic way of his, he was able to continually elude Nixon’s minions. Until, of course, the time he didn’t.

RU: So if there’s a movie (and I think there has to be), who would you have play Tim?

SD: I don’t know Hollywood very well. My wife says Owen Wilson. Who do you think?

The 60’s are over. I know because I’m a product of bat shit crazy people who really think they accomplished something, they just don’t have even a clue as to what that might be.

Quit whining.

anybody playing leary besides kyle maclachlan and the movie is immediately rendered a psy-op